Our final landscape surgery meeting of the autumn term focused on a recently begun project led from within Royal Holloway’s Centre for the GeoHumanities, An Oral History of the Environmental Movement in the UK, 1970-2020. Funded by the AHRC and running for three years (2022-25), the project will deliver a national archive of oral history testimony from 100 environmental activists and campaigners active within the UK between 1970 and 2020, to be housed at the British Library’s collection of National Life Stories within the National Sound Archive. The project team is led by Toby Butler as Principal Investigator, and includes Barbara Brayshay, Chris Church, Felix Driver, Jeremy Iles and Oli Mould, with a further post-doctoral researcher currently being appointed to join next year. That team membership provides a confluence of personal experience in environmental campaigning and practice (in particular from Chris and Jeremy) and varied academic expertise (in oral history, in archives and public geographies, in publicly focused and participatory mappings, and in activism).

The project is also collaborating with a number of partner organisations, including: National Life Stories / the British Library, to deliver the freely accessible sound archive of oral history testimony, catalogued, with fully searchable transcripts, and held in perpetuity; the Royal Geographical Society (with the IBG), to produce GCSE and A-level appropriate educational materials; and Friends of the Earth, to support the project’s networking and dissemination activities. The project’s advisory board reflects those partnerships as well as offering additional external expertise, comprising Professor Julian Agyeman (Tufts University, Co-founder of the Black Environment Network), Craig Bennett (CEO, Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts), Dr Julia Laite (cultural historian, Birkbeck / Raphael Samuel History Centre), Professor Jenny Pickerill (environmental geographer, University of Sheffield), Professor Joe Smith (RGS-IBG Director), Mary Stewart (Director of National Life Stories, National Sound Archive, the British Library), John Vidal (former environment editor for The Guardian) and Joanna Watson (Communications & Events Manager, Friends of the Earth). Furthermore, the project is currently developing its wider collaborative network with environmental organisations, with whom consultation and engagement will continue throughout.

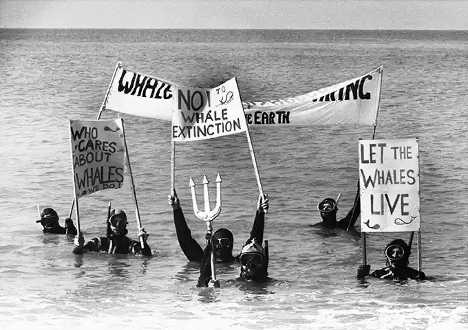

In advance of our meeting, the project team kindly shared with us a project summary and the ‘case for support’ from their grant application. Unless one is a research council peer reviewer then most grant applications that we see are our own, so Landscape Surgery is a space where we can share proposals within the group and talk about their development. Here, the careful crafting of the text was apparent, conveying with remarkable clarity the project’s aims, practices and intended contributions. To be honest, this blog post might have been best used simply to reproduce that text! But this clarity was more than a product of stylistic polishing; it also seemed to reflect the simple truth that this is a project that needs doing. In our meeting, the project team members talked through the origins of the project idea, how the team came together, the complex mechanics of the development of a great idea into a fully worked through AHRC application, and the project’s ambitions, both intellectual and cultural. Chris and Jeremy recounted how their initial planning began a decade ago; with the likes of Friends of the Earth UK and Greenpeace both founded in 1971, they recognised the cultural importance of documenting the lives of these environmentalists whilst their voices could still be heard. However, the ambition was more than simply documenting that past; by gaining testimony across the span of 1970-2020, and from the many different strands of the environmental movement of the last 50 years, it was to produce an enriched collective memory of the environmental movement in the UK. As Toby noted during the discussions, this will involve a variety of oral history dynamics, including the more typical engagement with the life stories of older people by younger generations, but also younger people recounting their more recent experiences to their elders. Both within the archival collection itself, and through wider public engagement activities, the project seeks to promote that intergenerational discussion.

The team also asked for input on key issues they are facing in the project’s early stages, particularly the ‘challenge of choosing’. Whilst creating an oral history archive of 100 testimonies is a huge endeavour, how to select just 100 voices is far from easy. Above all, the project aims to construct an innovative history of environmental activism over the last fifty years, situating the experience of activism within its biographical contexts and investigating links between family, region, class, ethnicity, gender and generation in the formation and careers of environmental campaigners. Its scope also reaches across multiple environmental concerns, including climate change and energy, transport and mobility transitions, wildlife and biodiversity, landscape, seascape, green and blue spaces, waste and recycling, and pollution. A key objective of the project is therefore to enable diverse and unsung voices to be heard. In part this means not only focusing on ‘the usual suspects’ or most famed; but it also means engaging critically with what is traditionally included within, and excluded from, the environmental movement, and exploring how that movement has been defined, and might have been defined differently, over the years. In sum, a polyvocal ethos is central to the work, with an emphasis both on collecting diverse voices and the careful curation of their shared presence within the archive.

Other issues discussed ranged from the methodological – in particular, with respect to the interviewing and archiving practices – to the conceptual. The question of the relations between the UK environmental movement and place — at all scales from the sensing body to local sites, cities, regions, nations, transnational connections and planetary imaginations — was one to which the team and the proposal was strongly attuned. Narrative life story interviews, Oli argued, offer a means to weave those scales together, and a site-based element to some of the planned ‘witness seminars’ (which would focus on how people have worked on specific environmental issues) was also being considered. On the archival practice, it was clear that the expertise of the team and National Life Stories will be invaluable in navigating the complicated ethics of consent and transparency involved in collecting personal testimonies for open and enduring access. More broadly, the project allowed us to return to discussions from earlier in the term’s programme, on archiving, participatory politics, and activism. Archival activism will be a core concern for the project, as will the politics and ethics of ‘national’ archive projects. The project is designed both to engage with calls for a more democratic, inclusive and diverse view of national history; and, through producing a nationally resourced collection, offer a level of sustainable accessibility that it is hard for community-based independent initiatives to achieve.

As well as the oral history and witness seminar collection housed by the National Sound Archive, the project is looking to deliver an open access book representing that collection, educational materials, media coverage and commentaries, and academic articles. The Surgery group looks forward to hearing more about the project’s progress over the next three years, and to its involvement of RHUL graduate students in a number of its activities. The project website, with links to its own blog, can be accessed here.

Philip Crang